Remembering the great pianist Maria Yudina

There are comparatively few biographies of great pianists — with reason, I always thought. Pianists didn’t seem to be especially interesting to read about, even great ones. I assumed it was because they were, after all, only performers, interpreters of other people’s work. Lacking the sweeping vision of creators, they could not be expected to articulate unique perspectives and couldn’t have had much of import to say to anyone who was not a professional musician. Their lives seemed bland even when they weren’t. The few such books that did come my way (including a biography of Glenn Gould, a pianist whose famously hyperkinetic interpretation of the Goldberg Variations and equally famous eccentricities got him more than his fair share of attention) were not so much exceptions that proved the rule as exceptions that showed why there was a rule in the first place. Then I discovered a book about Maria Yudina.

A Fiery Heart: Maria Yudina as Remembered by Contemporaries (Plameneyushee serdtse: Mariya Ven’yaminovna Yudina v vospominaniyakh sovremennikov), published in 2020 by Russia’s Center for Humanitarian Initiatives and untranslated into English, is mostly a collection of texts about Yudina written by those who knew her, along with a smattering of interviews and speeches. The tone of the book is borderline hagiographic, but in this case this is no objection — when nearly a hundred people write the same thing, with only insignificant variations, the representation of the theme is probably accurate. This is a book that will challenge anyone who believes pianists are uninteresting, and if I am not entirely ready to part with my preconceptions, it is because Yudina was more than just a great pianist. A couple was once overheard saying to each other after a Yudina concert that the experience had been something “out of this world.” The same can be said about Yudina. She did not live a life that was particularly colorful or rich with adventure; on the contrary, much of it was an exercise in asceticism. What made her life special was that it was lived for the benefit of others. Blowing to smithereens the Faulknerian dictum that “Ode on a Grecian Urn” was worth any number of old ladies, Yudina showed that turning one’s personal world into scorched earth and debris was not a sine qua non for a brilliant artist. When not playing music, she effectively served as a page-turner to the lives of those unable to play them out on their own. But that life, a life of endless sacrifices and perpetual self-abnegation, did not unfold in spite of her art. Both the life and the art came from the same burning flame — Yudina’s deep, intense religiosity. She was a unicorn, one of those rare people so sincere in their Christianity they appear to be saintly.

There was nothing preordained about it. She was born in 1899 in the Russian town of Nevel. Her family was Jewish but secular, and the father, a well-regarded doctor, was a total skeptic when it came to religion. According to the philosopher and scholar Mikhail Bakhtin, a lifelong friend of Yudina’s, the doctor was such a libertine spiritually that his daughter could have converted to Islam for all he cared. In the event, at age nineteen, Yudina converted to Russian Orthodoxy. In the post-revolutionary new order bent on institutionalizing atheism, the decision was inauspicious. But whatever prompted the conversion, it wasn’t whimsicality. A precocious adolescent, Yudina had strong intellectual inclinations and had read widely in a number of subjects, including philosophy; her reading fare included works by St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. Yudina’s milieu consisted of such illustrious figures as Mikhail Bakhtin, who would go on to become a towering figure in his own right. Yudina must have been more than prepared for her spiritual journey, and her chosen faith was a path she would never abandon. In the fiercely anti-theistic state engendered by the Bolshevik Revolution, adherence to one’s faith came with a price, especially if the adherence wasn’t closeted. Yudina never concealed her beliefs and was eventually booted out of the Leningrad Conservatory for having them — the administration had decided a religious professor in its midst was dangerous. And in a sense, it was. From the standpoint of ideological atheism, Yudina was toxic. For her, Christianity was not a Sunday-service event but a way of life. Most of us are content to live in Civitas Terrena; Yudina wanted to build a bridge to Civitas Dei. Always penniless, she was said to be the only pianist of her caliber who did not have her own piano. Whatever money and time she had was handed out to others. There were always the hungry to support, the ailing to take to the hospital, the politically repressed in need of intercession. One of her contemporaries writes about an army of beggars, some rather obnoxious, besieging Yudina when she left church. Yudina emptied her purse anyway. She would borrow money from those who had some to give it to those who had none, and she wasn’t always concerned that the debt be repaid; the borrower could simply lend the funds to someone else, thus perpetuating a virtuous cycle — a communal approach to property that was very Christian at heart.

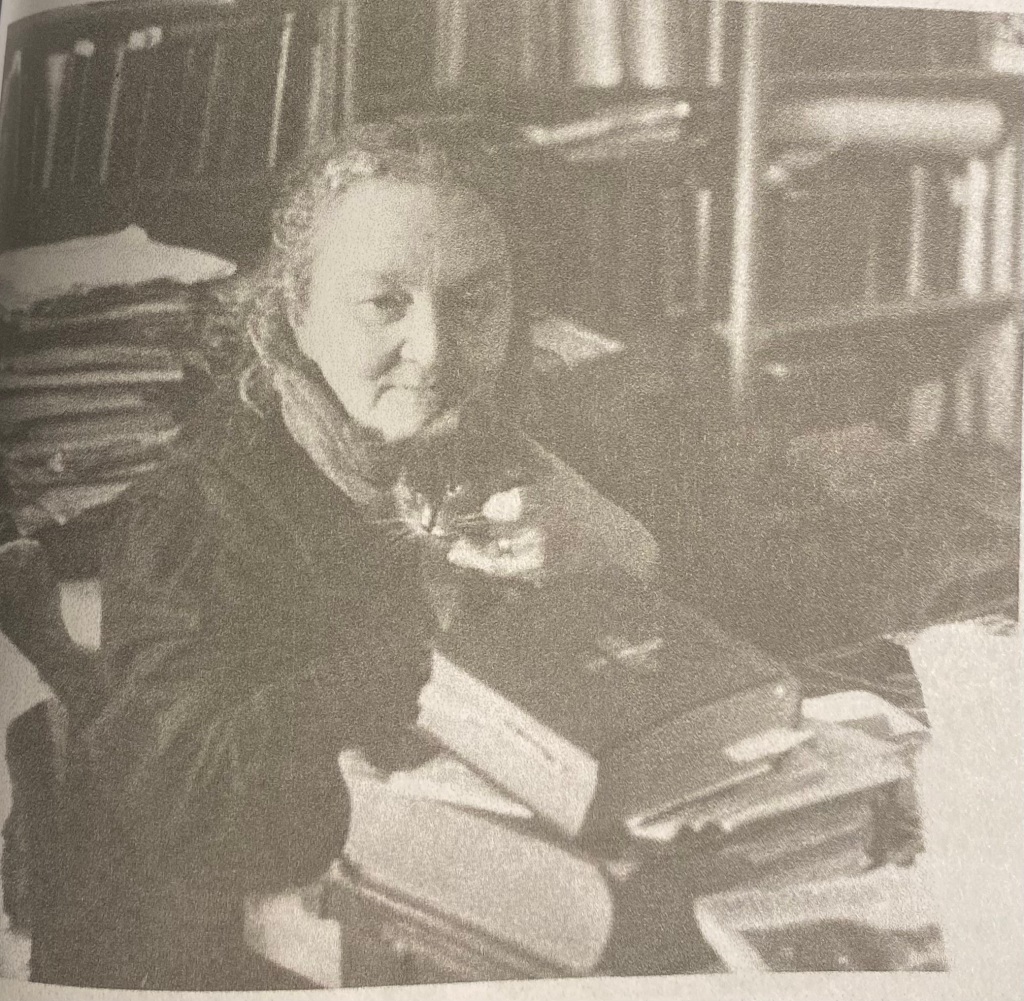

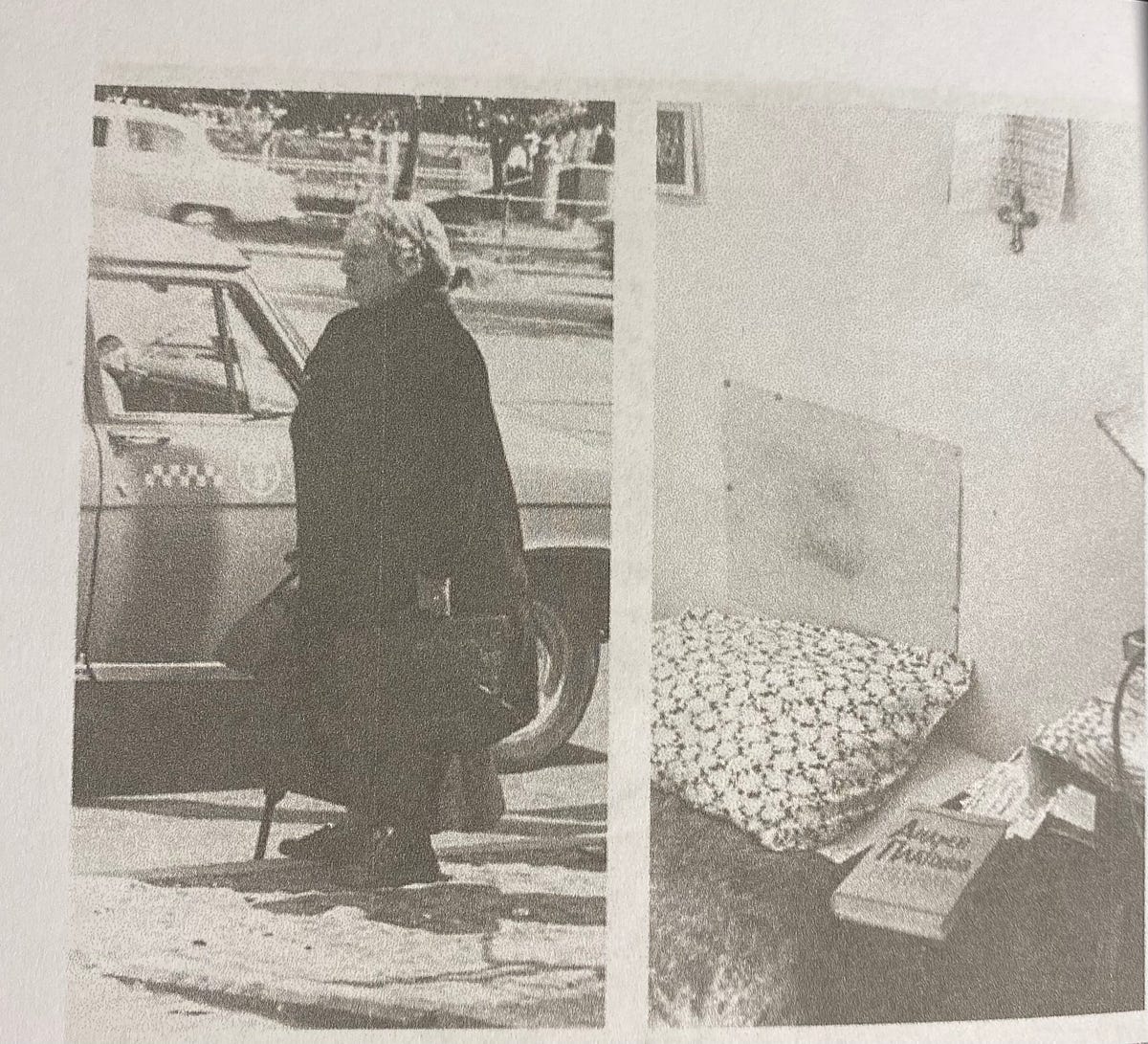

Unconcerned with material things, Yudina was not known for her sartorial elegance, and the word “nun” recurs throughout A Fiery Heart. She often appeared in loose-fitting black dresses that did little other than conceal her embonpoint, and her sneakers scandalized those with more exacting ideas about proper footwear. A photo of Yudina in her later years shows a dead ringer for the “Pigeon Lady” from one of the Home Alone movies. Those who visited Yudina at home were bewildered by her living quarters. There was hardly any furniture, cats were everywhere, and a park bench served as a sofa. Yudina slept on an iron affair called a soldier’s bed. An extant photo of a bedroom she inhabited in Moscow shows a Russian Orthodox cross hanging on the wall and a hardcover Platonov book lying on an uncomfortable-looking bed. It is hard to believe that one of the top Soviet pianists could live like that, harder still that living like that was a choice. Visitors to her home reported that Yudina never locked the front door. I can’t imagine this was only because there was nothing to steal. She must have believed in the goodness of others, and thought that if someone did pilfer something, it was only out of necessity.

The same austerity governed her private life, if one can speak of one. The reader meets only two men in the 600+ pages of A Fiery Heart. One is the half-French, half-Jewish Pumpyansky, who was part of the intellectual circle back in Nevel, and who, as a convert to Russian Orthodoxy, had a considerable influence on the young Yudina. Pumpyansky was highly gifted but very impractical, and the relationship went nowhere. The other man appeared years later, when Yudina was approaching middle age. He was a student of Yudina’s, some fifteen years her junior, and they became engaged. But the marriage never took place; the student went mountain climbing with friends and was killed in an accident with members of his party. Characteristically the grieving Yudina went to live with, and take care of, the ailing woman who was supposed to be her mother-in-law. There did not seem to be any other men in her life.

“Ne ot mira sego” — literally “not of this world” — is a Russian expression for impractical people ill suited to the demands of life. Although I am reluctant to describe someone who worked so tirelessly on behalf of others as “not of this world,” I suspect this is how Yudina was perceived by many and that that was what saved her in the end. The more prominent you were in the Soviet Union, the harder it was not to toe the party line. Yudina was not politically engaged, but she never toed the party line. Under Stalin independent spirits were usually done away with, and Yudina was nothing if not independent. She never shrank back from danger. During the Second World War, Yudina asked, in vain, to be sent to the front to take care of the wounded. She managed to make it to Saint Petersburg, then Leningrad and under a blockade, to play for the beleaguered population. During concerts she would read poems by ostracized poets such as Pasternak and Zabolotsky (whom she knew personally), testing the patience of both the concertgoers and the authorities. A cellist who collaborated with her writes how Yudina once announced that the work she was about to play — Beethoven’s Appassionata — had acquired “unnecessary associations.” She was alluding to what Lenin reportedly said about the piece — a work of genius, no doubt, but one couldn’t listen to it for long, since it made one want to stroke people’s heads, while the times called for hitting them. As far as the topic of Lenin and aesthetics is concerned, that is all there is to say, but you did not say it in public. As the cellist adds, anyone other than Yudina would not have made it home that night, not even in the more relaxed post-Stalin times.

The most famous story about Yudina’s audacity concerns Stalin himself. The Red Tsar was so taken with Yudina’s recording of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 that he sent her a pecuniary lagniappe. She allegedly replied with a peculiar note of thanks that informed the dictator some of the money had been donated to a monastery so that the monks could pray that Stalin be forgiven for all the evil he had done. If the story was invented — as it probably was, since Stalin was not in the habit of receiving dressing-downs from his subjects—it means no one thought it stretched credulity. Someone so headstrong and principled was bound to run into serious trouble sooner or later. Yudina never did. It’s true that she was ejected from various institutions and occasionally prevented from performing in public, but in a country where millions perished in camps, she got off easy. It was perhaps her reputation as the holy fool of Russia’s music world that persuaded the authorities to leave her alone.

What does any of this have to do with her art? For historical and cultural reasons, art in Russia was traditionally more than just art; it was, in fact, a form of religion. Concerned with the perennial questions of the soul, the greatest of Russia’s writers were not seen as craftsmen but preceptors and prophets, and venerated accordingly. This is especially true of the Dostoevsky-Tolstoy literary duumvirate. The authorities understood this, and the more totalitarian among Russian rulers always tried to subdue them. There is a reason why Stalin wanted Soviet writers to become “engineers of human souls” and why Yevtushenko said a poet was more than a poet in Russia. Unsurprisingly, the fate of Russian writers — from Radishchev in the 18th century to Pasternak, Solzhenitsyn, and Brodsky in the 20th — frequently resembled those of martyrs. Literature — poetry in particular — was seen less as recreation than spiritual sustenance. Those who lived through the chaotic years immediately following the Bolshevik Revolution wrote about half-starved people flocking to unheated concert halls where they sat huddled in their winter clothes just so they could hear some poetry (Yudina, too, performed in unheated concert halls during the war). Of course, Russian society was always text-centric, but the sacralization of art was not confined to literature. Let’s translate the full text of the final, sixth movement of Scriabin’s epic and epically neglected First Symphony (this is a literal translation, and I have made no effort to preserve the rhyme):

O wondrous image of the Divine,

The pure art of Harmony!

To you in friendship do we bring

The praise of rapturous feeling.

Of life you are a bright dream,

You are a fete, an inspiration,

Like a gift to people do you give

Your enchanting visions.

At that grim and cold hour,

When the soul is full of mayhem,

Man finds in you

The lively joy of consolation.

The powers felled by battle

You miraculously restore to life,

In a weary and ailing mind

You midwife scores of novel thoughts.

An endless ocean of feelings

You spawn in an adoring heart,

And the best song of songs sings

Your high priest, by you inspired.

Reigns over the world supremely

Your free and mighty spirit,

Man lifted by you

Commits an act of supreme courage.

Come, all the peoples of the world,

To sing the praises of Art!

Glory to art, glory forever!

This is an effusive hymn to art in which art acquires the form of religion. Yudina would have never agreed that it supplants religion, but I don’t doubt she would have endorsed the message. She believed that music was a higher calling meant to be served, music with a capital M — and indeed, the word is sometimes capitalized in A Fiery Heart, the way religions are. This is a very Russian phenomenon. Yudina would have found insulting the idea that being a musician was a job. She thought it was indecent for an artist to have money and thought nothing of playing an entire Beethoven piano sonata for an encore. Her conception of music was entirely religious. When Yudina performed Bach, whom she revered as a god, she named his Preludes and Fugues after parables from the New Testament. During a rare trip abroad, to Leipzig, East Germany, she is reported to have walked barefoot to the church that housed Bach’s remains, much like a pilgrim. She referred to one of Schubert’s Impromptus as a “hymn, a prayer.” Apropos of Beethoven’s 32 Variations: “Beethoven didn’t go to church, but God was in his soul.” Chopin’s 24 Preludes were not an expression of melancholy but “philosophical categories” that dealt with the theme of death and resurrection. A close friend of Yudina’s who had the opportunity to watch the pianist before her concerts writes that Yudina prepared herself before every appearance on stage as for a “sacred act.” Yudina’s professed belief in the immortality of great works of music mirrored the Christian belief in the immortality of the soul.

An amateur composer who knew Yudina describes a concert he once helped organize for her. She spent the first hour and a half reading parts from her own translation of Joseph Szigeti’s memoirs, followed by poetry by Vyacheslav Ivanov and Khlebnikov. She did some more reading after intermission, and when a furious cleaning lady barged into the hall at eleven, the concert was still in progress. The woman’s attempts to evict everyone were duly ignored, although Yudina wanted to compensate her later on. When the concert organizer called Yudina a few days later to complain that she had tired out the audience, Yudina retorted by asking how the faithful could stand in church for hours at a time on religious holidays. Yudina would not have made the comparison if she had regarded her concert merely as a form of leisure. It was a religious ceremony, she the priest, and the audience the worshipers. Those who had come to the concert must have sensed it too since, however exhausted, they stayed until the end.

Could this happen in a country where serious art is just a highbrow form of entertainment? At a recent Sokolov concert in Seville, I watched concertgoers file out of the auditorium like a herd of wildebeest while Sokolov, with his habitual generosity, treated the audience to a series of encores. Supposing Sokolov had decided to read some poems by Lorca for the first hour and a half? When I mentioned this to a Canadian acquaintance, he sided with the concertgoers. They had paid for the announced program, gotten their money’s worth, and it was time to go home. There were, after all, parking fees to pay, children to put to bed, and dinner to be enjoyed. While true, this is exactly the kind of thing the Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev had in mind when he wrote that music made it possible for the European bourgeoisie to gain quick entry into the heavenly kingdom, with no effort at all and for the measly price of twenty francs, only to return back to their prosy quotidian affairs a few hours later. Berdyaev was an implacable foe of bourgeois philistinism, and this denunciation of the European bourgeoisie smacks of spiritual elitism. But, in a sense, he was right. I recently watched a video in which a prominent music critic, whose expertise and taste are not in question, encouraged his Youtube viewers to have no sacred cows in music — audiences are consumers. This view of art as a form of entertainment to be consumed would have been incomprehensible to audiences huddled in their winter clothes in frigid concert halls while their empty bellies cascaded with borborygmi.

None of this is to be taken as a value judgment. The Seville concertgoers who cleared out before Sokolov was finished and Berdyaev’s European bourgeoisie crashing the gates of heaven for the price of twenty francs are not somehow culturally inferior. Nor do I intend to advance the usual tropes about Russian soulfulness, tropes that I dislike, especially when they are juxtaposed against the supposedly soulless West. This is just a question of different conceptions of what art is and ought to be. According to the “secular” conception — let’s call it that — art should come to you, on an on-demand kind of basis, and any effort on your part would be out of place. According to the other conception — the “religious one” — effort is required. God will not come to you if you don’t make demands upon yourself, and nor will art. Yudina epitomized the religious conception, and her faith suffused her art.

Those who heard Yudina live described her playing as hypnotic and mesmerizing. Unfortunately, this effect does not travel well via recordings, many of which are sadly of inferior quality. But that is not the only problem. Yudina’s penchant for doing things her own way meant she often broke with conventions, and the results were not to everyone’s taste. Several contemporaries write that Yudina had — surely a curious thing for someone endowed with a fiery heart — an analytical cast of mind, and it informed her interpretations. Detractors found them too intellectual. She was an enthusiastic champion of modern music, and anyone interested in Yudina’s art will have to wade through a fair amount of Hindemith, Bartók, and Stravinsky, some of it decidedly on the costive side. On the other hand, Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, and Debussy — the piano composers — found no place in Yudina’s repertoire. She disdained mannered music, meaning any music that had a salon-like quality to it. Thus, Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky were out (if the extant recordings are anything to go by, Yudina’s performance of Tchaikovsky was limited to his Piano Concerto No. 1); Mussorgsky and Shostakovich, in. To be sure, those whose tastes run along traditional lines will find Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven adequately represented, along with Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms. Her Schubert is lovely; the Mozart and Beethoven, superb. So is her Bach — Yudina’s Goldberg Variations deserve to be singled out for their remarkable crispness.

But when her analytical mind meets composers consumed by violent passions — I think here of Schumann and, despite his burgher-like façade, Brahms — things get more complicated. Her Kreisleriana is so emotionally charged it borders on the hysterical at times; Schumann was a stormy character, but more measured takes on the piece go a lot further. At the same time, Yudina’s lethargic 1951 interpretation of “Des Abends” (Fantasiestücke, Op. 12), nearly five minutes long, feels like someone had set the piece to play at half its normal speed; by comparison, Richter — a Schumann interpreter par excellence — needs only four minutes, while Cortot and Sofronitsky gallop through it in less than 3.5 minutes. Her live performance of Fantasie, Op. 17, is capricious and lacking in nuance; the second movement is especially wooden. Yudina’s 1954 interpretation of Brahms’s Piano Sonata No. 3 has nothing of the Brahmsian élan and is unlikely to be enjoyed by anyone who is not on the music equivalent of a diet. I wonder if Yudina even liked Brahms very much. (Admittedly, the interpretations I have heard might not be representative — even great pianists can have bad days. Also, Yudina’s interpretation of Brahms’s Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel is a screaming delight.) She certainly didn’t like Chopin, and although she did perform his Preludes, among other works, there is no trace of any Chopin recordings of hers online. In musical taste, Yudina was not omnivorous. That was her prerogative but, having listened to a good deal of Yudina, I must say that more “salon music” wouldn’t have hurt. I doubt any one of her interpretations, even those of Bach and Beethoven, will ever become a personal reference recording, and this is not merely on account of the poor quality of some of them.

Yet Yudina’s performances of Prokofiev’s Visions Fugitives and Medtner’s underappreciated “Sonata-Triad,” along with Taneyev’s Piano Quintet, are enchanting, and I think I can listen to them forever. Yudina the pianist has a way of touching the listener the way Yudina the person touched those who entered her orbit. There was something divine about the woman, and neither her art nor her life will leave anyone but a cold heart indifferent. Her death in 1970 seems to have been of a piece with the life she had lived. One finds two accounts of her passing in A Fiery Heart. Solzhenitsyn’s first wife, Natalya Reshetovskaya, took music lessons from Yudina, and Yudina was devastated when Reshetovskaya told her Solzhenitsyn wanted a divorce. She had a very dim view of divorce in general and usually severed links with anyone who walked away from a marriage. Solzhenitsyn was not just anyone. Yudina was positively crushed by the thought that the lodestar of the Russian intelligentsia could sully himself with divorce proceedings. After her student left, Yudina raced across town to discuss the situation with an acquaintance. She was dressed lightly, it was cold, and the asthmatic acquaintance had her windows wide open. Yudina came down with pneumonia, which, coupled with her diabetes, proved fatal. That is Reshetovskaya’s version.

Yudina’s nephew tells a somewhat different story, though here, too, Solzhenitsyn’s divorce surfaces as the culprit. In the nephew’s telling, Yudina was the one who had introduced Solzhenitsyn to the woman who would become his second wife. Apparently, the woman had come to Yudina seeking God; thanks to Yudina, she found Solzhenitsyn instead. According to the nephew, Yudina was so upset at having brokered the union, however unintentionally, that she had a nervous breakdown, which, coupled with her diabetes, proved fatal. Choose whichever version you like. In the end, Yudina died as she had lived — for others.

Yudina was a complex person. Even her contemporaries, who adored and loved her, let it slip here and there that the great pianist was not always easy to deal with. She could be obstinate, sententious, and quite overbearing at times. But there is no doubt she was genuinely a good person. At the same time, Yudina was also a “person of God.” Being a good person and a person of God is not the same thing. In one of his novels, the Russian writer Friedrich Gorenstein wrote that good people can’t be people of God. This is because they are too busy serving other people. People of God only serve God. Great people — prophets and geniuses — cannot be good people, since a good person inevitably attracts individuals who will make demands upon him and cause whatever talent or genius the good person possesses to dissipate. Put another way, a person who allows himself to be consumed by other destinies will be punished in some way, since he is not staying true to the destiny that is his own.

Did Yudina’s life refute the “Gorenstein Law”? Yudina was certainly conscious of the dangers of her goodness. Her nephew writes that she was plagued by a deep-seated fear that she would be asked on the doorstep of eternal life: “You could use your own means as you saw fit, but why did you help others using the means of strangers?” Yudina did not know how she’d answer that question. Perhaps, in a way, the question was put to her before she died. Despite the multitudes of people crowding her life, Yudina was lonely. At sixty she looked eighty and utterly spent. An interview with Bakhtin in A Fiery Heart reveals some thought Yudina’s playing had deteriorated in her later years. Bakhtin conceded her religiosity must have had something to do with it, though he was quick to add it wasn’t the piousness itself that was the problem, but its evolution from inward piousness to outward. Never a person of rude health, she suffered terribly in the last decades of her life. Aside from the diabetes, Yudina had trouble with her swollen legs, and peritonitis nearly carried her away circa 1960. Later she was run over by a car and sustained serious injuries, including some that were hand-related (the first thing she said upon regaining consciousness was that the accident had been her fault and not the driver’s, even though the fault was, in fact, the driver’s). One can’t help but wonder if she wouldn’t have fared better had she been a little less selfless.

Then again, plenty of self-involved people are lonely, too. Yudina’s playing might have deteriorated with time, but she made up for it by exercising her literary gifts, and the literary output of her later years is a testament to that. As for her health problems, they might have been caused in part by wartime privations. In the end, the question of whether Yudina was too generous with herself is the wrong question to ask, and you can be sure Yudina would have never asked it. What is one’s true destiny, and why can’t one’s destiny entail a life in the service of others? The many voices in A Fiery Heart, who pay homage to both the pianist and the woman, suggest that, in the end, Yudina proved Gorenstein wrong.

There was a macabre incident during Yudina’s funeral. When the coffin containing Yudina’s body was brought to the grave, it wouldn’t go in. There was a stone of some kind that prevented the coffin from being lowered. The gravediggers whose services had been retained and who were reassembled to deal with the problem were in their cups. It was dark and late by the time the coffin was finally swallowed by the grave and Yudina laid to rest. Those who write about the incident in A Fiery Heart see it as a symbol of her larger-than-life figure. The cynic in me is inclined to be less charitable. About the only thing this tragicomic coda to Yudina’s story— straight out of the darkly humorous prose of Sergei Dovlatov, that witty bard of life in the USSR — symbolizes is the absurdity of Soviet reality. But even the most diehard cynic will have to admit that the woman whose coffin could not fit into its grave had followed Paul’s exhortation to bear the burdens of others and thus fulfill the law of Christ (Galatians 6:2) to a tee. In this solipsistic age of Me-Me-Me, Yudina’s life is an example as well as a reprimand. And if most of us can’t live the way Yudina lived, we can at least celebrate her life by reading about her and listening to her recordings.