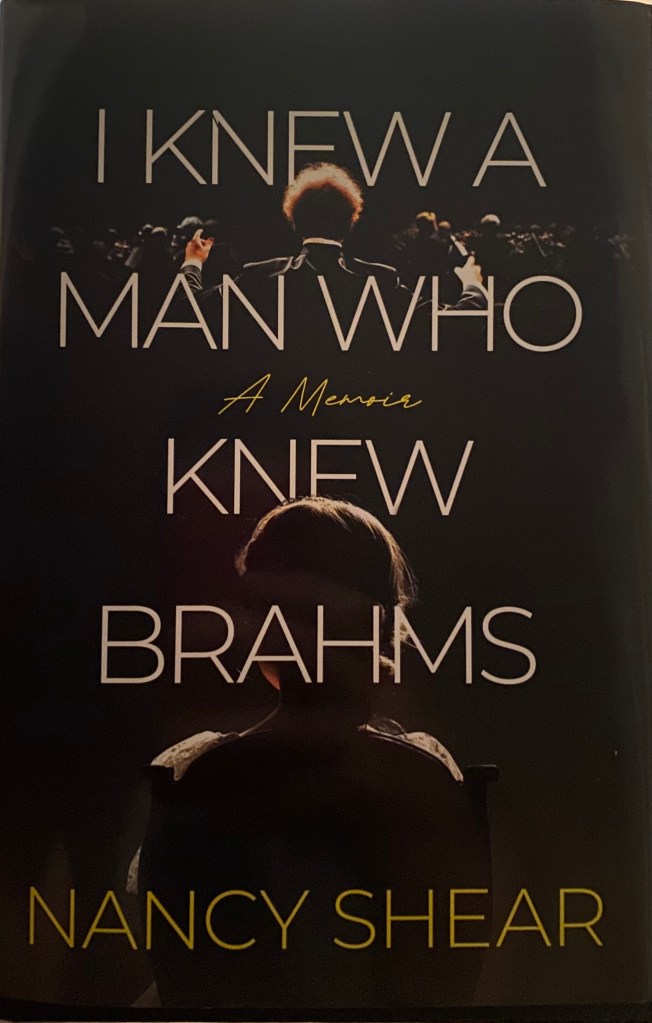

Book in the spotlight: I Knew a Man Who Knew Brahms by Nancy Shear

Eugene Ormandy, the great conductor and my namesake, was once shopping for a suit jacket at Brooks Brothers. Trying one on, Ormandy began to move his arms about to see whether it was comfortable to wear while conducting. The salesman asked, “What do you do, juggle?” Delivered in a footnote, this anecdote might well be the only truly memorable episode in Nancy Shear’s I Knew a Man Who Knew Brahms, a memoir fresh from the printing press. Let’s be fair: writing about the world of classical music is a thankless task. Brilliant musicians aren’t just unpleasant; in relation to their art, they are also not especially interesting. Unlike, say, with writers, knowledge of composers’ and performers’ personal lives will never enrich one’s understanding of their music. The identity of Beethoven’s “immortal beloved” does not add to the beauty of anything he may have composed to celebrate her; von Karajan’s association with the Third Reich does not lessen the depth of his symphonic interpretations; Sviatoslav Richter’s sexuality offers no clues to his virtuosity. Here, the art completely diminishes the artist, and it takes a powerful narrator to bring the artist to scale. Shear is not such a narrator, and despite the incontinent praise lavished on her memoir, the book is a potent reminder musicians are best heard and not read about.

While the title of this piece is clickbait (there is no sex in any orchestra pits, sorry), the title of Shear’s book is not. Shear did once shake hands with the son of a pharmacist who, as a young boy, had delivered meds to Brahms in person. But even if it were sheer clickbait, Shear would still have an interesting story to tell. Hers is the stuff sentimental Hollywood movies are made of. She came from a dysfunctional Philadelphia family that featured a paterfamilias so abusive Shear is unable to call him “Dad,” and a weak, permanently traumatized mother who was battered emotionally and perhaps even physically. At fourteen, Shear attended a concert conducted by the legendary Leopold Stokowski, and ended up falling in love with both classical music and Stokowski. Unable to afford tickets to hear the Philadelphia Orchestra, she began to sneak into the Academy of Music. Soon she came to know members of the renowned orchestra and, at the tender age of seventeen, was offered a job at the orchestra’s library, eventually becoming an orchestra librarian herself. The rest, as they say, is history – but it is not really Shear’s history. The ironic thing about this memoir is that, for all the author’s keenness on the advancement of women in the classical music world, its merit rests entirely on Shear’s connection to men. Namely, two outstanding men: Leopold Stokowski, the famed conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra; and Mstislav Rostropovich, Russia’s cellist extraordinaire.

Stokowski takes up the most amount of space. Whether all that space is warranted is an open question. Shear was very close to Stokowski but, due to their massive age difference (64 years) and Shear’s religious veneration of the conductor (as a young woman, she thought of him as a “deity” and was surprised that the “Maestro” engaged in such lowly bodily functions as washing), their May-December relationship was never consummated. This is doubtlessly a good thing: the few scenes in which the two get close to something approaching physical intimacy make for uncomfortable reading. Still, Shear remained in love – the platonic kind – with Stokowski long after the deity had fallen off his pedestal, and she does her best to paint a sympathetic picture of a man who arouses little sympathy. Stokowski may not have had the EQ of a Neanderthal, but the man Shear describes was anything but loveable. Mercurial, egotistical, and impetuous, he was given to throwing tantrums and exploiting others; even an orchestra librarian who admired him once said Stokowski sucked the blood out of people and then threw away the bones. Like many famous conductors, he was despotic and could summarily fire musicians who had families to feed, for no good reason. Like many extraordinary persons, Stokowski seemed to harbor insecurities and suffer from “arriviste syndrome”; he went through life cultivating a mythical aristocratic Polish background, going so far as to adopt a continental European accent and erase his parents from existence (Gloria Vanderbilt, Stokowski’s wife No. 3, had no idea her husband’s mother was still alive, even after having been married to him for ten years). His women and loved ones were sometimes treated abominably, not to speak of lesser mortals (Stokowski once invited Shear to celebrate Thanksgiving with him, tearing the young woman away from her family, but when she came over, he left her alone and went to have dinner with an orchestra patron), and Shear’s description of Stokowski’s last years at his British manor offers unflattering glimpses of life with the Minotaur. Perhaps towering figures like Stokowski deserve to be granted indulgences. Shear seems to believe that; she confesses to having once thought that great artists “were elevated beings who should be given license to do as they wished,” and she is prepared to plead the Maestro’s case. No objections, Your Honor. But the memoir is thin on what made Stokowski the great artist he surely was and what made him tick. The man whom Shear knew so well eludes her, and the conductor who propelled the Philadelphia Orchestra to national prominence eludes the reader. Shear’s emphases feel misplaced, and despite her noble attempt to share the man she admired so much with her readers, I found myself wishing she had kept him for herself.

The Slavically exotic “Slava” – Shear refers to Rostropovich by his diminutive Russian name – was the antipode of the aloof, patrician Stokowski. Jocular, gregarious, and as expansive as his native land, Rostropovich spoke with the accent of Russian mobsters in bad films, boozed it up, and liked to belch out expletives. He was never “Maestro,” just Slava. To his lasting credit, he was also a man of courage who spoke up against the Soviet system while he was in the Soviet system. At the same time, he was an exponent of that quintessentially Russian conception of art as a form of religion and of the artist as a martyr. “You not yet suffer enough to play this music!” he bellowed at a student who was not playing a Brahms cello sonata to his satisfaction. This attitude went hand in hand with the idea – also very Russian – that artists could not be judged by the standards of the hoi polloi and were not governed by the same moral laws. The corollary of this is that the suffering artist also made others suffer with him, something Shear learned the hard way. You wouldn’t know it by reading Vishnevskaya’s sanitized, PG-13 memoir Galina (I certainly didn’t), but the diva’s marriage to Rostropovich was a turbulent one, and he had affairs on the side (apparently, so did Vishnevskaya). One of his affairs was with Shear, who, as we find out, got to know Rostropovich in the biblical sense at a Washington hotel and then at the cellist’s apartment in New York. Though old enough to be her father, Rostropovich told Shear that the responsibility for their relationship rested with her, and he meant it. She would be callously abandoned in the streets of Philadelphia because Rostropovich ran into someone else, and she would have to wait eight hours in London for him to call, in vain. By the 1990s, their relationship had cooled, and Rostropovich turned a bit nasty. When Shear interviewed him in 2005, he arrived with a young female interpreter, even though they had never needed one before. The translator left a lipstick mark on her cup of tea; as Shear watched on, Rostropovich lifted the cup and kissed the mark. Oh, those artists . . . Of course, we only get Shear’s side of the story, and in any case, she insists she has no regrets. So much the better. Just like Stokowski, though, Rostropovich is inevitably dwarfed by his art, and stories of his pup having a gastric meltdown on an airplane cannot change that.

The back of the memoir’s dust jacket promises “a literary welcome mat to the beautiful world of classical music,” along with a visit to the “homes, studios, and minds of legendary artists.” That’s overselling it. There are certainly interesting tidbits for both neophytes and connoisseurs – I, for one, had no idea orchestras had their own librarians, nor did I know that Stokowski took liberties with scores, sometimes transposing music without notifying the audience the music had been tampered with. It was amusing to find out that, even in the bygone days of heavier cultural gravitas, concertgoers rushed for the exits before the musicians had had a chance to treat the audience to generous encores – some things never change. Ultimately, however, the memoir does not meet the expectations it sets. It is not that it is tedious or uninteresting; it just lacks sweep. Stokowski and Rostropovich are really the only people the reader meets, and the meeting feels awkward and protracted. There is a photo of Lorin Maazel in the book, but Shear never talks about him. She does talk a little bit about Ormandy, Stokowski’s successor at the Philadelphia Orchestra, whom she portrays as an unpleasant man and an underwhelming conductor. I am happy to believe the former; the latter is tendentious. Someone who served as conductor for one of the world’s best orchestras for more than four decades cannot be a mediocrity. The music critic Dave Hurwitz – whose taste and depth, despite his occasionally colorful rhetoric, are not in question – says that “Ormandy’s range of interest and repertoire was limitless” and that he never had a bad recording. Hurwitz would never agree with Shear’s low assessment of Rostropovich’s conducting skills, and nor would I – his recordings of Prokofiev’s Violin Concertos No. 1 and No. 2 (with the London Symphony Orchestra and Maxim Vengerov as soloist) and Tchaikovsky’s symphonies are ample proof that he knew how to wield a baton. Actually, you will learn more about Rostropovich from Hurwitz’s 14-minute-long Rostropovich Youtube video than from Shear’s 300+ page memoir. The passive, almost helpless tenor of the memoir – possibly the result of lingering effects of Shear’s childhood trauma – gets in the way of a compelling narrative, and the platitudinous final chapter, a brief rumination on the need for more diversity and inclusion in classical music, feels like it was written because this is what thoughtful readers expect thoughtful writers to write. The dust jacket proclaims that “no reader will ever listen to music the same way again”; I assure you the memoir will most definitely not change the way you listen to music after you turn the last page.

Speaking of the last page, it is a two-paragraph-long coda. Unlike the chapter that precedes it, the coda is both touching and glorious. Shear acknowledges that, in the end, the art will outlast its creators and interpreters, as it always does. Her hope is that somewhere in the afterlife she and her mother, possibly in the company of Stokowski and Rostropovich, will listen to their music as it reverberates through the universe – and this reader, however disappointed by the book he has just read, hopes her wish will be granted. And perhaps he ought to be more charitable in his review. As orchestras fold across North America, concert halls look increasingly like retirement homes, and classical music as a genre succumbs to the forces of Tocquevillean democratization, it is surely a good thing that books like this one are still published and talked about. In the words of Napoleon’s mother, pourvu que ça dure.