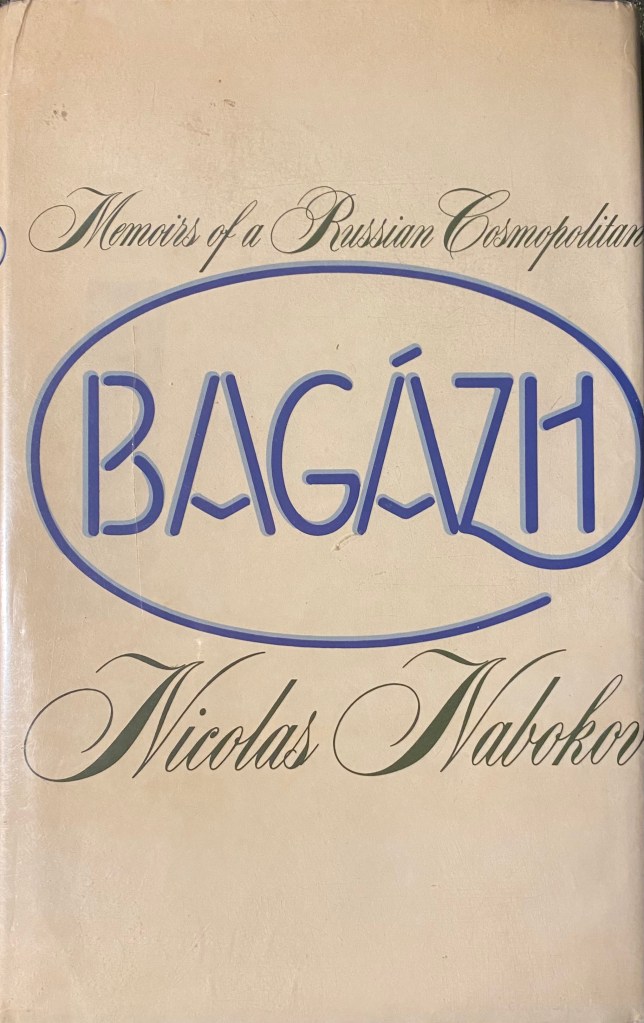

Book in the spotlight: Bagazh: Memoirs of a Russian Cosmopolitan by Nicolas Nabokov

Sharing a last name with a literary sensation is a mixed blessing when you want to write a book of your own. On the one hand, you get an advance that lets you soar above the teeming hordes of literary unknowns whose name is legion. On the other hand, you are relegated to the shadows from which you must desperately claim some of the spotlight, along with the right to your own identity. This was the predicament of Nicolas Nabokov. A composer who wanted to write a memoir, he also happened to be a cousin of that other Nabokov – the Nabokov. He went ahead anyway, and this is surely a very good thing. While I have yet to hear anyone complain that Nabokov’s music is performed too frequently, his Bagazh: Memoirs of a Russian Cosmopolitan reveals a gifted raconteur who does full justice to the Nabokov name. But the book is more than just a walk down the memory lane. In an age of mass migration and global instability, Nicolas Nabokov has much to tell us – and he tells it well.

The word bagazh is Russian for “luggage” (pilfered from French, it is pronounced in the French manner, by stressing the second syllable), and it is a perfect symbol of a vagabond’s life, the life of a man in exile. But Nabokov, who was born in what is now Belarus, did not become an exile; he was an exile ontologically. His mother came from a family of obscenely rich landowners; his maternal grandmother inhabited a castle in the Ukrainian steppes and owned a steamer, which by the standards of the age must have been like owning a private jet. His paternal side was equally illustrious: a grandfather was a minister during the reign of Alexander II; a grandmother was a baroness. When his mother remarried, it was to another landowner by the name of Nicolas von Peucker. This was tsarist Russia’s equivalent of the one percent, a demographic group that spoke French as well as it did Russian, if not better, and one that, to quote the Russian philosopher Pyotr Chaadayev, was forever flapping about in a sunbeam whose sun was the sun of the West. It was a social class that issued Russian cosmopolitans, who were the best kinds of cosmopolitans because, unlike West Europeans, they never took their Europeanness for granted. It is to that class that Russia owes its post-Petrine cultural masterpieces.

But Russian cosmopolitans were also, in some ways, not very Russian. Often their foreignness was literal – many in the upper crust had West European, typically Germanic, ancestry, and a cursory review of tsarist Russia’s Who’s Who will confirm this. But we don’t need to go that far; an examination of Nabokov’s own ancestry is sufficient. His mother descended from the Falz-Feins, a family of German colonists; his babushka – the baroness – was born Korff; his stepfather, von Peucker, is described as “part Balt, part Greek, and only a bit Russian.” As for the ancestry of the Nabokovs – traceable to the Mongol Khan, according to family lore – Nabokov speculates: “Maybe he was a Tartar, maybe he was a Persian, or an Arab, or an Armenian, or a Jew – and maybe he was indeed in the employ of the great Khan.” The exact identity is not important; what’s important is that Nabokov didn’t think the progenitor was Russian. Writing his insufferably indulgent memoirs in the 20th century, the Russian artist Alexandre Benois mentioned that he had not a drop of Russian blood and that “purely Russian elements” had not penetrated his family until the end of the 19th century; the “elements” are mentioned with a trace of disdain, and elsewhere Benois refers to “racial differences” between him and ethnic Russians.

Not everyone felt that way; Nabokov certainly does not, and he says he will always be a “Beloruss.” But, at the end of the memoir, he admits that architecturally Russian churches are “endemically alien” to him; the “onionry” of their domes are for “simple souls,” and he pines for the small churches of Byzantium or the kinds of churches one finds in the southwest of France. Besides, in matters of identity, how others see us is no less important than how we see ourselves. Even if Nabokov had been a “purely Russian element,” he was still foreign, for to be a Russian cosmopolitan was to have a European identity – an identity that was foisted on Russia by Peter the Great when he tried to graft Europe onto Russia by building a new imperial capital on the banks of the Neva. But the new identity never fully took root. The result of his reforms was deracinated European (or Europeanized) elites lording it over non-European (and certainly non-Europeanized), autochthonous masses. While this is perhaps a bit too black and white, the temptation among some historians to interpret the Russian Revolution as a revolt of the indigenous population against foreign elites is not entirely unreasonable. The restoration of Moscow as Russia’s capital – and the downgrading of Saint Petersburg, a city that, Benois wrote, was never seen as Russian by Russians – was the restoration of Muscovy and Asian Russia.

When Nabokov came into the world in 1903, the revolution was some years away. His early years in Russia are the subject of the first part of the book – the strongest of the three, perhaps because it is a rich portrait of a world forever gone. Nabokov received many blank checks, with little indication that he would never be able to cash them in. There were trips to various family estates, doting servants, and Shetland ponies as Christmas gifts. It was a charmed existence that obscured the looming conflagration. Not that Nabokov was unaware of his immense privilege. It did not escape him that those who were not “Kastelyane” (the people of the castle) lived amid grinding poverty and misery. He saw how the starosta (elder) shooed away beggars as his family entered the local church for worship. He was appalled by the conditions of the Jews who lived in the area. Nabokov touchingly describes Khristina, a lifelong companion of Babushka Nabokov, casually mentioning that the woman had been given to his grandmother as a “playmate serf” when the baroness was a child. Once Nabokov witnessed his stepfather strike the head coachman in the face during an argument. Shortly after that episode, someone set a cowshed and a hayloft on the estate on fire. Then the whole country was on fire. Nabokov was able to get out with his mother, as did most members of the Nabokov clan, including the baroness and her devoted servant. Others were not so lucky. Nabokov’s maternal grandmother – the one with her own steamer – was murdered by Cheka henchmen, who had no qualms about shooting an eighty-seven-year-old woman.

The second part of the book covers Nabokov’s European years – the interregnum between the two world wars. The Nabokovs settled in Berlin, then a mecca for Russian émigrés. They had lost everything in the revolution, but not their resilience and indomitable fortitude, proving that being an aristocrat is as much about having privilege as making do in its absence. Debonair and urbane, Nabokov moved about in star-studded cultural circles in Berlin and Paris as he tried to make a name for himself in the world of music. He got to know Diaghilev and Stravinsky; the former gave the budding composer his first big break, while the latter became a personal friend (a charming antediluvian recording available on Youtube shows the two musicians trying to enjoy a few unguarded moments in a Hamburg room). He partied with Sergei Yesenin and dined with Rainer Maria Rilke; at the time, the brutish Yesenin was busy abusing Isadora Duncan in Berlin’s seedy cabarets, while Rilke had taken an unhealthy interest in Lenin – poets can be brilliant, but they are rarely clever. Prokofiev, Hindemith, and Cocteau were among friends and acquaintances. Last but not least, there was his cousin Vladimir. The future author of Lolita was then busy writing some of his best works under the name of Sirin, to avoid being mistaken for his father, a prominent liberal politician. The two cousins spent a lot of time together, and Nicolas and Vladimir’s sister Elena fell in love with each other (“le cousinage est un dangereux voisinage,” we read in Tolstoy’s War and Peace). There was talk of marriage. But it was not to be. The marriage never took place; Vladimir’s father was killed while valiantly protecting another prominent liberal figure from Black Hundred assassins; Berlin ceased to be a cosmopolitan, tolerant city; and Nabokov packed his bags and left for America in 1933, the year Hitler came to power.

The American chapter of his life makes up the last part of the book. While interesting in its own way, it is the least satisfying of the three – Nabokov may have been too close to the period to write about it with the necessary detachment. Like many exponents of the Old World, he has mixed feelings about America. He admires America’s openness and hospitality, but its brashness and lack of interest in culture bring out the snob in him. He got a job teaching at an American college and spent the ensuing years in academe, though he continued to compose. There were new friends. Isaiah Berlin was one. W.H. Auden was another; the British poet appears to have influenced Nabokov considerably, inspiring him to enlist in the US army during the war and head to the European theater. After the war, Nabokov became involved in political activism. He had no illusions about Stalinism and clearly saw that it was a close relation of Nazism; he felt it was incumbent upon him to do something about it. This led Nabokov into some dubious ventures. When he and other like-minded individuals crashed a Soviet propaganda event held at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in 1949, Nabokov embarrassed Shostakovich, who was one of the Soviet attendees, by asking for his opinion about an odious propaganda piece in the newspaper Pravda – publicly and rather gratuitously. Some years later, Nabokov became one of the faces of an organization that promoted cultural initiatives in Europe; it was only later that Nabokov found out the organization was financed with CIA money. Artists rarely have much to gain when they change lanes.

There is some discussion of music in the memoir, but Nabokov takes care not to talk too much about his craft. This is just as well – he is much more interesting as a cosmopolitan than as a composer. It is Nabokov’s cosmopolitanism that fascinates and makes his memoir so topical. For the Bolsheviks, he was little more than a tsarist fossil, a relic of a bygone age; they did not have a clue. Nabokov was thoroughly modern, for to be modern today is to be a person with bagazh. He would have understood our own time, a world of refugees and expats, migrants and digital nomads, globalization and jumbo jets. He knew what it was like to experience great upheavals, to live in the flux of history, and to be marked by rootlessness. The cosmopolitan, the man with bagazh, is at the heart of the modern condition, and Nabokov shows us how to survive it. He shows us what it’s like to be buffeted by the winds of history and to lose everything overnight, yet still maintain one’s decorum and sense of humor. He shows us how to keep one’s sense of identity in a world in which identities are consigned to perpetual fluidity. He shows us how, figuratively speaking, in the age of bagazh one can pack one’s bags.

Nabokov wears his culture light. He was a gentleman; he certainly reads like one. To write like a gentleman means to avoid being boring or didactic. Nabokov is neither, and this makes it easy for the reader to overlook the memoir’s flaws and imperfections. While he is anything but prudish (he relates at length a conversation with his maternal grandmother, who took it upon herself to tell the pubescent boy about the birds and the bees – in a way no reader will ever forget), he never reveals more than is necessary, and the text is largely free of offenses against good taste. We learn that Nabokov is not cut out for monogamy, but he mentions his numerous marriages only in passing and avoids settling scores. The writing is vivid and elegant; I must single out a charming description of a journey on horse-drawn sleighs on a cold winter’s day. Nabokov is a past master of delightful turns of phrase (Isadora Duncan reminds him of a “Roman matron after revels”), and sometimes the prose is altogether Nabokovian (faced with a malfunctioning shaver’s socket at a Moscow hotel, Nabokov shaved “Gillettingly”). There is even an unintrusive tip for dealing with gastric ailments, supposedly borrowed from Schiller (rotting pears).

The memoir ends with Nabokov’s visit to the Soviet Union in 1967. He had been invited there by Soviet diplomatic officials he had gotten to know during his cultural activities in postwar Berlin. The trip was Nabokov’s homecoming; he had now come full circle. The memoir ends where it began. But the experience was bittersweet, and he satirizes the drabness and manifold absurdities of Soviet life. He had come to recover a paradise that was lost, and of course he never found it. Looking at the Kremlin towers, he thought of a poem by Akhmatova: “Like the Strelty’s wives, / I shall wail below the Kremlin towers.” Nabokov asks, “Did she write those lines here in Moscow, after trying to pass under one of those hideous towers? To see whom? To ask for mercy from whom?” From whom? The “Kremlin Caucasian,” as Osip Mandelstam called Stalin in one of his poems, who else. As his wife, Nadezhda Mandelstam, writes in her memoirs, the triumph of Stalinism represented the triumph of Asian Russia and the defeat of the European one. When Nabokov glanced at the Kremlin towers one last time, he saw the loss of this European Russia to which he was permanently attached and which he knew would never be resurrected. The sprig of wilted forget-me-nots left for Nabokov by a Moscow hotel maid, appearing in the last sentence of the third part, is a subtle symbol of his memories.

But the memories themselves – Nabokov’s memories – will never fade. In the epilogue, an elegiac letter to a Soviet diplomat called “A Postscript to Russia,” Nabokov says that it is his memories that keep European Russia alive and its heart beating. “I’m like a Jew in the early Diaspora, praying for ‘next year in Jerusalem.’ My Jerusalem is St. Petersburg. And I know it will never happen, it cannot possibly happen, and yet I pray for it . . .” Saint Petersburg was now known as Leningrad, but for Nabokov it would forever be Saint Petersburg. He died in 1978, three years after Bagazh was published. Had he lived for another thirteen years, he would have seen the erstwhile imperial capital, that most European city of Russia, restored to its original name. Does it mean his prayer was answered? Not really. It is unlikely that post-Soviet Russia would have been very much to Nabokov’s taste. Nabokov’s Russia passed into history and, sadly, so did Nabokov and his kind. Writing about a German patron of the arts he knew, Nabokov referred to the man as “the last of a breed.” He wouldn’t have found a better epitaph for himself.